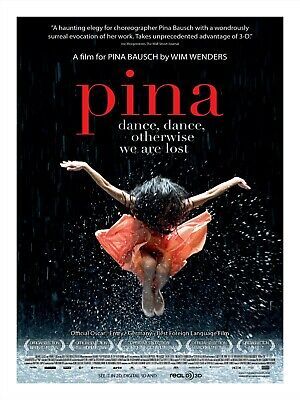

a FILM by WIM WENDERS in homage to PINA BAUSCH

PINA is not only one of the first European 3D movies to be made, it is also the world’s first 3D dance film. Under the disguise of film, PINA is less a documentary than Wenders’ heartfelt tribute to the late revolutionary choreographer, Pina Bausch—celebration of her genius in the art of creating dance. For the third time since HAMMETT where Wenders tried out Coppola’s electronic studio and BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB with his first high-resolution digital film, Wenders is once again helming the vanguard of cinematic technical development with the filming of a dance documentary in 3D. Through PINA, Wenders has rendered contemporary dance accessible to the general public, considering how controversial Bausch was as a choreographer, framing images in an inviting way that draws viewers closer instead of alienating them without compromising the potent effect of the dance.

PINA interlaces performance footage of Tanzteather Wuppertal with interviews Wenders conducted with Bausch’s longtime dancers. Devoid of plot, narration, and chronological structure, what began as a work about Bausch turned into a work dedicated to her. Upon asked on his most memorable moment of the film, Wenders commented it was towards the end of the shooting process when he realized the great accomplishment of 3D as its capacity to show volume and to take audience into the world on screen in a much more immersive way as never before. The idea of PINA came about rather unexpectedly in 1985 when Wim Wenders was deeply moved by his first encounter with Pina Bausch’s “Café Müller” in Venice. Five minutes into the show, Wim found himself weeping helplessly, overcame by an emotion he had never experienced at a staged performance. His body understood instantly enough what was being enacted well before his brain could interpret what was happening on stage. Out of the first meeting with Bausch after that revelatory experience, Wim decided that he would one day make a film together with Pina.

That one day lasted a good 20 years. At the beginning, Wenders had no idea how to film dance even after studying all sorts of dance films. Compared to the dancers who are imbued with such freedom, energy, physicality and vivacity, Wenders found the cameras to be at a loss in front of the stage, himself equally clueless on how to capture Bausch’s repertoire appropriately on film. Whatever he imagined would fall short in reality as he felt there was an invisible wall between what he could do and what Pina’s dancers were achieving on stage. What could be put on screen falls severely short of the same excitement one experiences at a live performance. Up till then, dance is known to be a language all on its own, occupying space which is exactly what film lacks in its representation. Space has always just been imaginary on film. Cameras have been thrown out of windows, put on planes, helicopters, cars, rails and cranes but the result would always be nothing more than the compression of space onto a two dimensional screen. On conventional film, an audience could merely look into an aquarium wherein the dancers are the fish, but Wenders craved to be in their element –to be in the water. More than just a distanced spectator, Wenders wanted to be in the same realm as the dancers.

For many years, Wenders was deterred by the inadequacy of film to translate Bausch’s unique art of movement, gesture, speech and music onto screen. He needed a medium that would interpret dance succinctly through Bausch’s eyes, deploying her language to the fullest. The more he looked through the history of dance film, the bigger his problem became. Bausch understood because she had been involved in a couple of recordings of her work and she knew that something did not really draw together between film and dance. She could relate to that invisible wall that Wenders referred to but was not discouraged by it. She was confident that together, she and Wenders would find a language for how to film dance.

Prior to PINA, Wim Wenders had been known in the field to have pioneered digital technology “out of necessity,” in his 1997 groundbreaking documentary THE BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB on Cuban music. Necessity again brought Wenders to chance upon 3D when it came to chronicling Pina Bausch’s legacy. The Eureka moment came for Wenders when he saw Catherine Owens’ and Mark Pellington’s 2007 concert documentary U2 3D about the Irish Rock band’s concert film in 3D. Seeing that film opened a huge pathway for Wim as it gave him a way into the missing space, a way to see dance from the inside out, which was particularly useful in exploring Bausch’s oeuvre which was less concerned about aesthetics than it was about life, sorrow and love, all the frailty that a human embodies. 3D became the perfect tool for Wenders to express Bausch’s artistic motifs through the language of the film. Only by incorporating the dimension of space could Wim bring her work succinctly into film.

In early 2009, Wenders, together with Bausch and the Tanztheater Wuppertal, began the phase of actual pre-production of the film. After half a year of intensive work, and only two days short of the planned 3D rehearsal shoot, Pina Bausch passed away suddenly. Shocked and grief-stricken, Wim Wenders halted all preparations, convinced that the movie could no longer proceed without her. However, after two months of mourning, the dancers who were just about to start rehearsing the pieces selected for the film approached Wenders and convinced him to continue the project. After all Bausch was more than the main character, she was the reason itself to make the film. Her piercing gaze lingered on the movements of her ensemble and every detail of her choreography is very much still alive and distinctly inscribed onto their bodies. Despite the devastating loss of Bausch’s departure, it became even more urgent and crucial to record her works on film.

Since then, Wenders changed the whole concept of the film radically from a joint film co-directed with Bausch to a tribute for her. It was only through these dancers that Wenders was able to take the audience into the world of Pina Bausch. More than Wenders, the dancers needed desperately to realize the project for they needed to find a way to say their goodbyes to Bausch. She had passed on so abruptly that none of them were able to do that in person. Wenders realized then that he himself wanted to thank Bausch and bid her goodbye. The film was now the only outlet to do so. Mounting Bausch’s dance on film became more important for the living than as homage to Pina Bausch.

Over a period of time Wenders and the dancers selected several of Bausch’s repertoire that put together, would make a fitting tribute to her. Wenders stuck by the ground rules Bausch had established: no interviews, no biographical data, just the work. Bausch didn’t want the film to be about herself, about her childhood or how she learned to dance – she just wanted it to be about the work. Although Bausch had never seen 3D, she was very adamant that her choreography be directed to the audience. Crossing the border between the stage and the viewer is an important part of her choreography where the dancers are constantly engaged with the audience, even physically coming down the stage. It has always been important for Bausch that her pieces are completed first in the direct senses and feelings of the audience. Wenders was given the permission to shoot from left and right and center and high and low, but if possible, no reverse angles. As much as Wenders and his team strived to conquer the third dimension, they hope to avert the audience’s attention to their very conquest of space at the same time. As the camera glides into the dance space like a virtual participant in the action, the plasticity should not call attention to itself, but should make itself almost invisible, so that the dance assumes its primacy and becomes even more evident.

Wenders’ use of the 3D technique is tantamount to the success of PINA; he is fully aware of the seduction of 3D to have objects flying and people moving into the audience space but chooses instead to exploit the technique just enough for the bodies to be voluptuous and movements to be organic, as if a live theater stage is enacted right before the screen’s borders. For the unique requirements of the shoot of PINA, Alain Derobe, the film’s stereographer, developed a special 3D camera rig mounted on a crane. To create the depth of the room the camera has to be positioned between the dancers, close enough to follow them and to literally dance with them. Hence each film crew member had to internalize the choreography by knowing exactly where the dancers would move so the camera would not be in their way.

It took a little over two years to prepare and a year to shoot PINA. In addition to excerpts from the four productions of “Café Müller”, “Le Sacre du printemps”, “Vollmond” and “Kontakthof” which Pina Bausch has originally intended to include, Wenders has carefully selected archive footage of Bausch at work as well as short solo performances by the dancers of the ensemble. To achieve this as a means of expressing their memories of the choreographer, Wenders employed Bausch’s distinctive method of questioning as choreographing where she would have her dancers answer her posed questions not in words, but with improvised dance and their own body language. Wenders filmed these different solos, innovatively inserted in the 3D world of the film as a third element, in numerous locations in and around Wuppertal, where the dance company has been based for the last 30 years as a way of recognizing that a dance can make itself at home anywhere.

To date, PINA has been shown all over the world and grossed $20 million (U.S.), drawing huge audiences from all walks of life. The film went on to garner multiple international film awards including an Oscar nomination for best documentary feature. PINA has opened up Bausch’s work to countless audience who would otherwise never had the opportunity to experience it firsthand, not to mention even heard of her name. Tanztheater Wuppertal is currently preparing a performance of 10 of Bausch’s repertoire to take place in London in conjunction with the Olympics 2012. It is by far the company’s biggest performance commission in 30 years. Wenders is convinced that documentary as a film genre will be uplifted to a whole new level by 3D and the fact that this new language is now no longer a tool for big budget studio movies alone. As much as dance theatre on film in 3D is a challenge, it heralds the future of dance as a widely accessible art form. With such kinesthetically visual sensation more powerful than any intellectual reflection, dance on film has braved a whole new frontier with 3D.

References:

- Corliss, Richard. “Wenders’ Pina: Dance Crazy.” TIME Entertainment: What’s Good, bad and Happening, from Pop Culture to High Culture. N.p., 29 12 2011. Web. 4 Mar 2012. http://entertainment.time.com/2011/12/29/wenders-pina-dance-crazy/.

- Keefe, Terry. “Wim Wenders on Pina: Capture the Spirit of a Dance Legend with 3D.” HUFF POST ARTS . N.p., 19 12 2011. Web. 4 Mar 2012. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/terry-keefe/wim-wenders-pina_b_1154920.html?ref=arts&ir=Arts .

- Lane, Anthony. “Theatre on Film.” The New Yorker. N.p., 19 12 2011. Web. 4 Mar 2012. http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/cinema/2011/12/19/111219crci_cinema_lane .

- Melnik, Meredith. “Director Wim Wenders on Filming the Work of Pina Bausch in 3D.” TIME Entertainment: What’s Good, bad and Happening, from Pop Culture to High Culture. N.p., 22 12 2011. Web. 4 Mar 2012. .

- Rosenberg, Douglas. “Video Space: A Site for Choreography.” The MIT Press: Leonardo. 33. 4 (2000): pp. 275-280.

- Quill, Greg. “Wim Wenders reinvents 3D in epic dance film.” Toronto.com: Turn up Your Downtime. N.p., 09 09 2011. Web. 4 Mar 2012. .